Nearly 28 years after the Narasimha Rao government initiated economic reforms, there are still some acts / legislation that stifle production and impede growth. Chief among these are the Hank Yarn Packing Order introduced way back in 1974. Handloom Reservation Order and inflexible labour laws such as engaging a worker for more than 48 hours a week, employing women in night shifts etc., They have outlived their utility and should be scrapped altogether to pave the way for smooth operation of industrial units in the country.

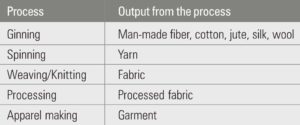

Against this background, the spinning segment of the textiles industry has a reason to cheer. The obligation on it to pack, in hank form, 40 per cent of yarn to ensure availability to the de-centralised handloom sector stands reduced to 30 per cent, according to a recent Central Government decision. The move comes nearly 16 years after a cut in the obligation level to 40 per cent in 2003 from 50 per cent when it was first imposed under the hank yarn packing obligation way back in 1974.

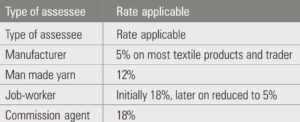

What were the factors that prompted the decision? First hank yarn was found to be used by small units for dyeing purposes using more water. Secondly these units could not adhere to the pollution norms that mandated zero liquid discharge and preferred to buy cone yarn like the handlooms after GST was imposed on hank yarn. The obligation has had no effect on productivity of handlooms. Moreover, only about 30 per cent of handlooms had been using hank yarn.

Originally, the obligation covered cotton and viscose yarn, but is now applicable only to cotton yarn, since viscose yarn was got removed from the Essential Commodities Act. Imagine! The obligation is still being continued despite the recommendations of the Abid Hussain Committee in 1985 and the Sathyam Committee in 1999. The Textile Commissioners office in Mumbai had also suggested scrapping of the obligation. The Sathyam Panel had found the obligation to be an “avoidable” burden on the spinning industry and suggested some viable and more effective alternatives to ensure sufficient yarn supplies to the handloom sector. The Textile Commissioner’s office conducted a study a few years ago which revealed that nearly 40 per cent of hank yarn produced in the country was used by the powerloom sector and not the handloom sector for which it was meant. The actual requirement of yarn for the handloom sector is difficult to assess on the basis of handlooms fabrics production.

The government claims that with the strict enforcement of the Hank yarn Packing Notification issued by the Textile Commissioner, it is ensured that actual packing of hank yarn is sufficient to meet the total requirement of hank yarn. Despite the government’s claims, hank yarn gets diverted to the powerlooms sector. This takes place though the action invites lodging of FIRs against defaulting mills by the Textile Commissioner’s Office. It is known that operation in the handloom sector have become unviable. So the alternative is to train handloom weavers and shift them to the powerloom sector or any other sector.

Spinning is a capital –intensive industry and is very important for the value-added industry to develop and thrive. Currently, the country has 52.45 mn spindles and 8.76 lakh rotors spinning capacity. There is a 30 per cent excess capacity of cotton yarn for exports, which rose by 18.57 per cent to $3,255.87 mn in April – January 2019 from $2,745.85 mn in the corresponding period last year as per the latest data available.

As has been stated earlier in these columns the fabric segment is weak and operates on obsolete technology and depends on government doles. This has been hampering the demand for yarn and supply for garments and home textiles. Fabrics production has gradually come down to less than 5 per cent from as high as 70 per cent in 1951. The decline is attributed to labour relations and government policies. Fabrics production has to be brought back to the organised sector by abolishing sops for the decentralised sector.

The need of the hour is consolidation and modernisation of the fabrics sector. Modernisation of weaving and processing also needs focus, besides encouraging production of indigenous shuttleless looms and phase out a large number of shuttle looms, which are still being used in the country.

The need of the hour is consolidation and modernisation of the fabrics sector. Modernisation of weaving and processing also needs focus, besides encouraging production of indigenous shuttleless looms and phase out a large number of shuttle looms, which are still being used in the country.

Reverting to handlooms again, there are 11 products reserved for production exclusively in this sector. If an Indian powerloom or mill produces any of them, the owner will be prosecuted. But a powerloom or a mill in any other country can produce them and export  to India in many cases with zero duty or concessional duty facility. This is obviously “irrational.” If these products can be competitively produced in handlooms, the reservation is not necessary. If they cannot, the reservation only induces inefficiency in production. It is felt that a conscious effort should be made to identify those products which can be competitively produced in the handlooms sector and it should be encouraged to produce those items. Many of the items currently reserved for the sector have scope for growth, both in the domestic and global markets and the reservation is hindering conversion of this potential into performance. The handloom reservation act should therefore be repealed to ensure unhindered growth of the fabrics sector. The garments and home textile sector also suffer from fragmentation. Consolidation of the fragmented textile and clothing units into organised ones will need substantial investment in land, building and machinery. A positive encouragement is to grant liberal loans and working capital at affordable interest. As per terms loans, the Technology Upgradation Fund Scheme (TUFS) can help handle this problem to some extent. In respect working capital loans, the industry faces problems both in the availability of funds and interest rates.

to India in many cases with zero duty or concessional duty facility. This is obviously “irrational.” If these products can be competitively produced in handlooms, the reservation is not necessary. If they cannot, the reservation only induces inefficiency in production. It is felt that a conscious effort should be made to identify those products which can be competitively produced in the handlooms sector and it should be encouraged to produce those items. Many of the items currently reserved for the sector have scope for growth, both in the domestic and global markets and the reservation is hindering conversion of this potential into performance. The handloom reservation act should therefore be repealed to ensure unhindered growth of the fabrics sector. The garments and home textile sector also suffer from fragmentation. Consolidation of the fragmented textile and clothing units into organised ones will need substantial investment in land, building and machinery. A positive encouragement is to grant liberal loans and working capital at affordable interest. As per terms loans, the Technology Upgradation Fund Scheme (TUFS) can help handle this problem to some extent. In respect working capital loans, the industry faces problems both in the availability of funds and interest rates.

It needs no reiteration that there is no alternative to liberalisation of our labour laws, if garments and home textiles have to be ungraded to world standards and empowered to compete effectively. The labour laws prohibit deployment of women at night shift, engaging a worker for more than 48 hours a week and temporary appointment of workers for seasonal jobs.

Further across making unit needs governments’ prior permission for closing its operations, if it employs more than 100 workers. This provision hurt both employees and employers and needs to be liberalised. A political will has to be developed for revamping the labour laws. Countries such as Bangladesh, Turkey and Cambodia have successfully developed their apparel and textiles sectors, leveraging their duty free access status to the US and the European Union which are the largest consumption bases. India does not have duty free access to these markets which gives other countries a major competitive edge over India.

The textile and clothing industry currently accounts for over 4 per cent of the country’s GDP, 14 per cent of industrial production and nearly 12 per cent of exports. It employs 35 mn directly and another 45 mn indirectly, thus emerging as the largest employer in the manufacturing sector of the country. It is also pertinent that the textile industry provides jobs mostly to uneducated and poor rural workers, especially women. The sector plays an important role in our society as clothing is next only to food among the primary requirements of the masses.

Despite such impressive contribution to the economy and the society, the textiles industry has not received the attention that it deserves from the governments in the past. India’s major competitors in the global market are China (For fabrics, home textiles and garments) Bangladesh (for garments) and Pakistan (For yarn and home textiles) There are several other Asian Countries that have registered impressive increase in their exports of textiles products in recent years.

China’s cost of textiles production remains high enough, losing the competitive edge of lower cost of production in recent months. Its growth in the textile and apparels trade has declined after the economic crisis in 2009. Thus the coming years present a very potential window of opportunity to our textile industry to increase its global share considerably. But this opportunity will have to be converted into export performance in a short period of time before our other countries to do so.